John Paul Jones was born on July 6th 1747. He was the son of a landscape gardener, and his first home was in the Arbigland House, in Scotland. At the age of 13, John Paul was indentured to an English ship-owner and served on board the ship Friendship. He loved the sea and was an excellent student. At age of 19, he became First Mate of the brig Two Friends, of Kingston, Jamaica. At the age of 21 (in 1768) he was appointed Master of Supercargo of the brig John, of Liverpool.

In 1773, Jones became involved in an argument with a mutinying Tobagon seaman. In the fight that ensued, he ran the seaman through with his sword. Instead of awaiting trial by a visiting admiralty court, he decided to leave for America where his brother William lived and had a tailoring business. But when he arrived in Philadelphia, he discovered that his brother had just died. Jones settled in Philadelphia and came to view America as his new home.

In 1775 Jones offered his naval services to the newly formed American Navy, known as the “Continental Navy”. In the same year, he became first Lieutenant of the 28-gun ship Alfred. Shortly afterward, because of his excellent leadership skills, he was given the command of the 12 gun sloop Providence. During a period of twelve months, he managed to capture 24 British merchant ships.

In 1775 Jones offered his naval services to the newly formed American Navy, known as the “Continental Navy”. In the same year, he became first Lieutenant of the 28-gun ship Alfred. Shortly afterward, because of his excellent leadership skills, he was given the command of the 12 gun sloop Providence. During a period of twelve months, he managed to capture 24 British merchant ships.In 1777 he was commissioned as a full captain and given the command of the 18 gun sloop Ranger. In 1778, while operating from his base in France, he successfully attacked a number of English harbors and towns and even captured the Royal Navy’s 16- gun sloop Drake in sight of hundreds of spectators on a nearby shore. Building on his military success, he developed a new strategy. Instead of trying to break the blockade on the US by the Royal Navy, he would take the war to the British shores.

In a letter to Le Ray de Chaumont (the French father of the American Revolution), Jones wrote: “I wish to have no connection with any ship that does not sail fast, for I intend to go in harm’s way…”.

While still living in Philadelphia, Jones developed a close friendship with Benjamin Franklin. Franklin used his influence with the French court to assign to Jones a 14-year-old 900 ton French East India merchant ship, the Duc de Duras. Jones re-named the ship the Bonhomme Richard in honor of his friend Benjamin Franklin, who at the time was printing the French translation of his popular “Poor Richard’s Almanac” which was translated in French to “Conseils pour faire fotune, la Science du bonhomme Richard”.

While still living in Philadelphia, Jones developed a close friendship with Benjamin Franklin. Franklin used his influence with the French court to assign to Jones a 14-year-old 900 ton French East India merchant ship, the Duc de Duras. Jones re-named the ship the Bonhomme Richard in honor of his friend Benjamin Franklin, who at the time was printing the French translation of his popular “Poor Richard’s Almanac” which was translated in French to “Conseils pour faire fotune, la Science du bonhomme Richard”.Jones refitted his new ship with 34 guns (including 6 old 18- pounders) and went out to sea again. This was to be his voyage into renown.

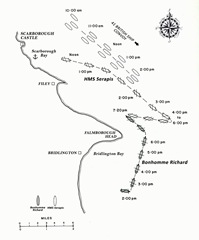

On August 14th, 1779 and now with the rank of Commodore, Jones was assigned the command of a squadron of seven American and French ships. His plan was to conduct a raiding cruise around the coast of Britain. Shortly after departure, two of the French vessels the Granville and Monsieur left the squadron to pursue their own targets, a third vessel the Le Cerf was separated because of fog.

For the next five weeks, the four remaining ships, (1) the 34-gun frigate Bonhomme Richard under Captain Paul Jones, (2) the 36-gun US frigate Alliance under Captain Pierre Landais, (3) the 32-gun French frigate Pallas under Captain Denis Cottineau, and (4) the 12-gun French brig Vengeance under captain Philippe Ricot, attacked British harbors and captured a number of British ships including two military supply vessels which were on their way to America.

By the third week of September, the squadron sailed to Ireland and the coast of Scotland and even attacked Edinburgh. They then turned southeastward to the northeast coast of England and headed on to rendezvous at Flamborough Head on the Yorkshire coast.

By the third week of September, the squadron sailed to Ireland and the coast of Scotland and even attacked Edinburgh. They then turned southeastward to the northeast coast of England and headed on to rendezvous at Flamborough Head on the Yorkshire coast.Thursday September 23rd, 1779 in the Morning

On Thursday morning, a convoy of 41 British ships was sailing on a northeastern course down the Yorkshire coast. The ships were carrying supplies from the Baltic to the Royal Dockyards in Southern England. It was escorted by two Royal Navy warships: the 20-gun Countess of Scarborough under commander Thomas Piercy, and the 44-gun ship Serapis under Captain Richard Pearson.

On Thursday morning, a convoy of 41 British ships was sailing on a northeastern course down the Yorkshire coast. The ships were carrying supplies from the Baltic to the Royal Dockyards in Southern England. It was escorted by two Royal Navy warships: the 20-gun Countess of Scarborough under commander Thomas Piercy, and the 44-gun ship Serapis under Captain Richard Pearson.As they passed the town of Scarborough, Pearson of the Serapis noticed a red flag on the ruins of the old Scarborough castle. After sending a boat to inquire about the warning, Pearson discovered that a squadron of enemy ships under the command of John Paul Jones was in the area.

Thursday September 23rd, in the afternoon

By 2:30 pm the front ships of the convoy had reached Flamborough Head. They saw the topsails of Paul Jones’

squadron about nine miles to the south. As the Serapis got closer, Pearson saw the ships and suspected that they belonged to the American raiding squadron. Pearson then fired a signal gun and ordered the convoy to turn towards Scarborough Bay where they would be safe under the guns of the Scarborough castle.

squadron about nine miles to the south. As the Serapis got closer, Pearson saw the ships and suspected that they belonged to the American raiding squadron. Pearson then fired a signal gun and ordered the convoy to turn towards Scarborough Bay where they would be safe under the guns of the Scarborough castle.By 4:00 pm, Pearson got a good view of the Bonhomme Richard. He signaled to the Countess of Scarborough to come closer and make preparations for battle. Pearson also orders that the ship’s colors (flag) be nailed to the mast, letting his crew know that he would not surrender.

Thursday September 23rd, in the evening

By 6:00 pm as the sun was setting behind the cliffs of Flamborough Head, Jones evaluated the Serapis through his

telescope and formulated a plan of attack. He instructed his officers Sub-Lieutenant James O’Kelly and Eugene Macarthy, of the French Regiment Comte de Walsh, a Gunner’s Mate John Kibly, and two-quarter gunners in charge of the sixty men manning the six old 18-pounders to open fire with double loaded round-shot into the hull of the Serapis.

telescope and formulated a plan of attack. He instructed his officers Sub-Lieutenant James O’Kelly and Eugene Macarthy, of the French Regiment Comte de Walsh, a Gunner’s Mate John Kibly, and two-quarter gunners in charge of the sixty men manning the six old 18-pounders to open fire with double loaded round-shot into the hull of the Serapis.The officers responsible for the twenty-eight 12-pounders on the upper deck, French Volunteer Lieutenant -Colonel Antoine Wuibert de Mezzieres, and First Lieutenant, Richard Dale assisted by gunner Henry Gardiner were ordered to fire double-headed shot and chain shot into the rigging of the Serapis in order to disable her ability to sail. Jones was hoping to repeat his success capturing the HMS Drake by disabling her rigging.

The officers in charge of the forty seamen and French marines stationed on top of the Richard were instructed to concentrate on clearing the tops of the Serapis and once successful, to start firing on its top deck.

Midshipman Jonas Caswell with eight seaman and French Marines was stationed in the fore-top (a platform on the front mast). Midshipman Nathaniel Fanning, with Lieutenant Edward Stack of the Regiment de Walsh and eighteen seamen and French marines, was stationed on the main-top (a platform on the main mast), Midshipmen Robert Coram with thirteen seaman and French marines was stationed on the back-top.

French Volunteer Colonel Paul Chamillard was assigned twenty-five French marines and told to take a position on the tallest platform on the back of the ship (called the poop deck) and fire at the deck of the Serapis. This distribution of snipers along the masts of the Richard and their excellent marksmanship would turn out to be critical in the battle to come.

The midshipmen John Mayrand and John Linthwaite remained on deck with Jones and acted as his personal aids (aides-de-camp).

By 7:15 pm under a starry night, the two ships approached each other. Pearson called the Richard from around 100 yards and said: “This is His Majesty’s Ship Serapis, what ship is this?”Jones remained calm and trying to prolong the element of surprise he replied: “Princess Royal” (a merchant ship that looked similar to the Richard). Pearson spoke again, “Where from?” Jones replied, “I can’t hear what you say.” Pearson asked again, “Tell me instantly from whence you came and who you be, or I’ll fire a broadside into you!”

By 7:15 pm under a starry night, the two ships approached each other. Pearson called the Richard from around 100 yards and said: “This is His Majesty’s Ship Serapis, what ship is this?”Jones remained calm and trying to prolong the element of surprise he replied: “Princess Royal” (a merchant ship that looked similar to the Richard). Pearson spoke again, “Where from?” Jones replied, “I can’t hear what you say.” Pearson asked again, “Tell me instantly from whence you came and who you be, or I’ll fire a broadside into you!”In response, Jones raised the American Continental Navy Stars and Stripes. Serapis ran out her big guns and opened fire.

For the first broadside, the Serapis double loaded its 18-pounders (two shells per cannon) and fired at the American ship. Throwing 465 pounds of steel from around 25 yards meant that the shells completely smashed the hull of the Richard and exited through the other side.

The well trained and disciplined Royal Navy crew of the Serapis loaded and fired much faster than the Richard could. In less than five minutes, the Serapis fired a second broadside.

Next it was the turn of the Richard, her guns were sponged, loaded rammed, primed, run out and fired. But as the Richard fired disaster struck. An explosion shocked the whole ship from below deck when two of the six old 18-pounders exploded causing damage to both the ship side and the deck above. In the explosion, Sub-Lieutenant O’Kelly was killed and many of the gun crews were also killed or wounded.

When Jones learned that the cannons exploded, he ordered that the remaining 18-pounders not be used (because of the fear that they would rupture as well). This further reduced the firing power of the Richard. The prospects for Jones did not look good. His 14-year-old ship armed now with a single battery of 12-pounders was fighting against the brand new English double-decker armed with 18-pounders which also loaded and maneuvered faster. It was only a question of time before the Serpais would blow the Richard to pieces.

The Serapis continued to fire two additional broadsides into the Richard causing additional heavy damage and destroying Richard’s existing gun batteries. By this point, its stern was smashed into a pulp. Her upper deck was covered with destroyed wreckage and dismounted guns. More then sixty men lay dead and seventy more were wounded. Jones later wrote “She made dreadful havoc among our crew… our men fell in all parts of the ship by scores…”

The Serapis continued to fire two additional broadsides into the Richard causing additional heavy damage and destroying Richard’s existing gun batteries. By this point, its stern was smashed into a pulp. Her upper deck was covered with destroyed wreckage and dismounted guns. More then sixty men lay dead and seventy more were wounded. Jones later wrote “She made dreadful havoc among our crew… our men fell in all parts of the ship by scores…”The Serapis approached the Richard again and fired a fourth broadside into her. Jones realized that his tactic of firing grape and chain shots to destroy the Serapis’ rigging

had failed. The Serapis was faster “out sailing us by two feet to one.” The Richard was also taking on water from large cannon holes at its water line and was settling lower (which made her less maneuverable). Jones’s only hope was to attach himself to the Serapis on the next pass and try to board her.

had failed. The Serapis was faster “out sailing us by two feet to one.” The Richard was also taking on water from large cannon holes at its water line and was settling lower (which made her less maneuverable). Jones’s only hope was to attach himself to the Serapis on the next pass and try to board her. The Serapis attempting to maneuver for a fifth broadside shot got close to the Richard but ended up colliding with her, the two ships were now connected side by side and as a result, the guns of the Serapis could not fire because their ports were forced shut during the collision. When it became clear that the Serapis was trying to disengage itself, Jones ordered as many as 50 grappling hooks to be thrown over to keep her connected.

The Serapis attempting to maneuver for a fifth broadside shot got close to the Richard but ended up colliding with her, the two ships were now connected side by side and as a result, the guns of the Serapis could not fire because their ports were forced shut during the collision. When it became clear that the Serapis was trying to disengage itself, Jones ordered as many as 50 grappling hooks to be thrown over to keep her connected.The Serapis was also now in bad shape. Sails, rigging, and even the areas between decks were ablaze. Because of the steady fire from Richard’s snipers located on the top-masts, no crew member dared to climb to the upper decks to extinguish the fires.

As an almost inexplicable sideshow, Captain Landais of the Alliance approached the area to assist the Richard, but both times that the Alliance shot at the Serapis, its shots hit the Richard too causing it damage and casualties. Jones would later write to Benjamin Franklin that “Either Captain Landais or myself is highly criminal, and one or the other must be punished”. Landais, turned out to be the criminal, and was eventually relieved from his command.

At this point in the fight, Jones began manning the guns himself and even successfully cut down Serapis’ main mast. Unfortunately, by then the Richard also started to show signs of actively sinking. Its master Carpenter realized that the vessel was beyond repair and ran to report the bad news to his captain. When he and one of the gunners failed to locate Jones, they assumed he was dead and called for the crew to “strike the colors”, or surrender. Jones, who wasn’t actually dead, heard this and became enraged and chased those who called for striking with a pistol in hand shouting “shoot them, kill them!”. According to this British myth, Jones fired his pistol at Lieutenant Grubb and then hurled it at another individual hitting him in the head and knocking him unconscious.

Meanwhile, Pearson on the Serapis overheard the cries and yelled over to Jones to confirm his wish to surrender. The famous reply he is quoted to have said at this point: “I have not yet begun to fight” is apparently inaccurate. Instead, Jones’ yelled back “No; I’ll sink, but I’m damned if I’ll strike!”

Meanwhile, Pearson on the Serapis overheard the cries and yelled over to Jones to confirm his wish to surrender. The famous reply he is quoted to have said at this point: “I have not yet begun to fight” is apparently inaccurate. Instead, Jones’ yelled back “No; I’ll sink, but I’m damned if I’ll strike!”After that, the ships renewed fighting. Some men from the Serapis tried to board the Richard and engaged in hand to hand combat, but the Richard’s crew drove them back to their ship. With almost half the crew dead or seriously injured, and the ship taking water, Jones made the decision to release the prisoners on board the Richard and put them to work pumping water and extinguishing fires.

Then, in one decisive moment, Jones organized a final boarding attempt. One of the boarding party members, William Hamilton, climbed up on the Serapis and tossed a few grenades onto one of

her open gun ports or hatches. He hit the bullseye! The grenade exploded right next to a series of black powder cartridges that were lying on the gun deck. The ensuing explosion almost completely destroyed the entire side of the Searpis. Pearson, seeing the futility of continuing further resistance, stroke his colors. He and his First Lieutenant, John Wright, then crossed onto Richard’s deck and formally surrendered.

her open gun ports or hatches. He hit the bullseye! The grenade exploded right next to a series of black powder cartridges that were lying on the gun deck. The ensuing explosion almost completely destroyed the entire side of the Searpis. Pearson, seeing the futility of continuing further resistance, stroke his colors. He and his First Lieutenant, John Wright, then crossed onto Richard’s deck and formally surrendered.Thursday September 23rd, at night

By 11:15 pm the two crews disc0nected the grapples that held the ships together. The Richard drifted away from the Serapis. As it moved, the Serapis lost its support and its main mast crashed over the side and went under water. The Serapis was also ablaze and both crews desperately fought all night to put the fires down. When dawn broke at 6:00 am, the fires on the deck of the Serapis were finally extinguished. The crew of the Richard in a desperate attempt to lighten the ship started throwing 18-pound cannons off the side.

Friday September 24th, in the morning

By 8:00 am, Jones realized that the Richard was still sinking. Jones called a meeting with Pearson and the other officers to workout a salvage plan. Both crews worked desperately to refloat her, but the exhausted crews could not pump the water out fast enough.

Friday September 24th, in the afternoon

By 2:00 pm, Jones, Pearson, and the other British officers all moved onto the Serapis. The Richard was inspected one more time and it was then decided that she could not be saved. With every minute that passed, she was in more and more danger of going under. At 7:00 pm, Jones ordered that all of the wounded on the Richard be carried off and taken to the Serapis. All vital supplies were taken off the ship and the remaining seamen stopped attempting to pump the water. As the sea and waves rose (about 6-10 feet), the Richard started sinking faster.

Saturday September 25th in the Morning

In the morning at about 6:00 am, Jones ordered the remaining crew of the Richard to abandon ship, as the water was almost up

to her gun decks. Jones knew that the Richard could sink at any moment. But even though he left all of his personal papers and money on board, he did not want to risk the lives of any crew member. He commanded his men to get their oars and pull clear as quickly as possible from the sinking ship. At about 10:30 am, on Saturday, September 25, 1779, John Paul Jones watched from the quarterdeck of the Serapis as the Richard went under, with her American Continental Navy flag still flying from her mainmast.

to her gun decks. Jones knew that the Richard could sink at any moment. But even though he left all of his personal papers and money on board, he did not want to risk the lives of any crew member. He commanded his men to get their oars and pull clear as quickly as possible from the sinking ship. At about 10:30 am, on Saturday, September 25, 1779, John Paul Jones watched from the quarterdeck of the Serapis as the Richard went under, with her American Continental Navy flag still flying from her mainmast.After the battle, Jones sailed the disabled Serapis to Texel (in Holland), but as soon as he arrives. British and French diplomats demanded that the Dutch government hand the ship over to them. Eventually, the French took possession of it.

Jones, was denied his rightful prize and had to return to the US on board the Alliance. A year after his return, one of his officers John Mayrant wrote him a letter inquiring about the prize money that the entire crew deserved, Jones replied with the following correspondence:

To John Mayrant [from JPJ]

L’ Orient July 23 rd, 1780

Dear Sir,

I had the honor to receive one or two letters from Amsterdam respecting Prize Money just before I left Paris… …In answer I must inform you that no part of the Prize Money has been or is in my possession. The Prizes are sold; but Mr. Chaumont does not appear disposed to part with the money, though he has had 100,000 Livers of it in his hands since the month of November last. Messr’s Goulade & Moylan have a letter of Agency from the crews of the Bon Homme Richard and Alliance; and they aught in consequence be Accountable forthwith for their proportion of the Prizes. They are furnished with lists of the Names and Qualities [ranks] of every person who sailed in those two ships from Groa; and the rules of the Navy of the United States with which they have been also furnished must determine the share due to each individual. I wish it was in my power to give you a more satisfactory account, I have done & will also do my best to procure justice to every person whom I had or may have the honor to command ; to procure the free --- of the last Prizes was my only business at Paris. You will be pleased to communicate this letter with my compliments to your brother officers who did me the honor to serve under my command. I hope they will excuse my not writing particular answers to each of them as I have very little time.

I am, with regard, Sir, Your most Humble Servant

South Carolina

Fairfield District

It seems that history is not without a sense of irony. Just like the Richard, the Serapis eventually also met a tragic end. Several years after the famous battle, the French navy commissioned the Serapis, under Captain Roche, to fight the British in India. Roche sailed his ship to fort Isle Saint Marie, off the northern coast of Madagascar. While Roche was ashore, a lieutenant and a sailor went below deck to obtain the daily brandy ration for the crew. While they were diluting the brandy with water, their lantern fell into the vat and set the entire locker on fire. Attempts to extinguish the fire failed and after two-and-a-half hours, the flames eventually reached the powder magazine (where black powder was kept) and the resulting explosion blew out the stern and the vessel sank.

Click to order a full-size version of the battle detail poster

References

Don C. Seitz, John Paul Jones his exploits in English seas

Reginald De Koven, The Life, and Letters of John Paul Jones

Search for the Bohnomme Richard, Salvage Hunters

Jones, John Paul Cottage Museum, Report to Benjamin Franklin

Jean Boudriot, John Paul Jones and the Bonhomme Richard

Peter Force Collection, John Paul Jones Manuscripts

You put so much work and effort in this essay Sheva - two thumbs up!!!

ReplyDeleteShe did, Yael. We've been working together on this for several weeks now and seeing it all put together here is very gratifying.

ReplyDeleteIt was some amazing battle that up until the last moments really looked impossible for Jones to win. That he never was recompensed for his efforts as he had been promised is such an irony under the circumstances.

Excellent post.Thanks ........

ReplyDeleteGreat job!

ReplyDeleteTom Mayrant

GGG Grandson of Midshipman John Mayrant

tmayrant@verizon.net